Jim’s Guide for Unit 9

Goal: Stable and Predictable Growth (Business Cycle)

Earlier we looked at the issue of growth in the economy. We decided that a society wants an increasing amount of goods and services, and so growth in real GDP was our first major macro economic goal. But there are good ways to grow and not-so-good ways for an economy to grow. The history of all market-based economies shows that while most economies grow from year-to-year, they clearly don’t always grow at a constant rate. Some years result in rapid, fast growth, while other years result in little or no growth. Sometimes economies don’t grow at all and actually shrink. That is, they produce a smaller amount of goods instead of a larger amount. Fortunately, positive growth happens more often than negative growth (fewer goods). This tendency of capitalist, market-based economies to sometimes grow and sometimes shrink is the business cycle. It is sometimes also referred to as a boom-and-bust cycle.

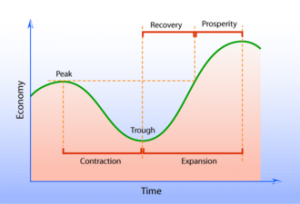

What economists refer to as the “business cycle” is, in fact, this tendency of market-based economies toward inconsistent growth, including occasional negative growth. A simple graph of real GDP over time reveals this up-and-down tendency. What we call the “business cycle” is the perception that economies repeat this up-and-down tendency. Economists have given names to the various phases of the business cycle as shown in this stylized diagram/graph of a hypothetical economy. A contraction that lasts for at least 2 consecutive quarters (6 months) is often called a recession. The green line going up and down is supposed to represent the total amount of real GDP over time. This particular diagram is highly stylized in that in real-life, economies usually spend more time (years) growing (going up) than they do shrinking (declining). In other words, contractions tend to be short-lived and measured in a few quarters of a year, while expansions tend to be longer-lived. Indeed, in the over 60 years of modern U.S. experience since World War II, the average contraction period has only been 8-9 months long, while the expansions are measured in years. The three most recent expansion periods have averaged approximately 6-8 years long.

Roller coasters may be interesting and fun rides at an amusement park (though not for me!), but when it comes to the economy, most people think stable and predictable is best. One of the most negative aspects of an economy experiencing the business cycle is that the cycle is itself unpredictable. It’s bad enough that real GDP declines during the contraction phase. But what really makes the business cycle an undesirable phenomenon is that it is so unpredictable. We never know when the contraction or decline is coming. We never know in advance how deep the contraction will be. We never know how fast we will recover. The business cycle makes it difficult for business people and ordinary consumers to plan their lives. The uncertainty created by the business cycle means people don’t whether to spend now and invest and take risks, whether it’s smarter to wait and save money for a “rainy day” when they lose their jobs or profits in the next recession.

Our last major macro economic goal, then, is to avoid the extreme ups-and-downs of the business cycle. Ideally, we want macroeconomic policies that help us avoid ever having a contraction or recession. Unfortunately, history demonstrates that despite such an ideal outcome is out-of-reach. Indeed, it is often remarked among economists that one of the surest signs that a contraction is imminent is that financial advisors on Wall Street and government advisors begin suggesting that we have “permanently ended the business cycle”. One leading Wall Street economist stated in early 1929 that the economy had achieved a new “permanently high plateau” of performance. Unfortunately for him, his remarks came only weeks before the stock market collapsed and the U.S. entered the Great Depression, the worst and longest recession in U.S. history.

What’s a Recession? What’s a Depression?

Technically, any decline in real GDP and the real economy, no matter how long, is called a contraction. If a contraction lasts for a prolonged period, a group of academic research economists will “officially” declare the contraction to be a recession and they will identify the “official” starting and ending months of the recession. The definition of what is necessary for a contraction to be “officially a recession” depends upon the country. In many countries and in the U.S. until 1978 a “recession” required at least two consecutive quarters (6 months) of declining GDP. In the U.S., though, the definition changed in 1978 to “a period of prolonged, broad-based economic decline as evidenced by several indicators”. In other words, even though real GDP might not technically decline for 6 consecutive months, if all the other indicators of economic activity such as employment, consumption, investment, and industrial production are declining, then a “recession” is declared. The original purpose of identifying recessions was to make economic research easier by having all economists call the same time periods a recession, instead of having economists doing research with differing dates. However, the term eventually became popular on both Wall Street and with politicians, with both these groups often not understanding it. For example, politicians currently in office like to promote the idea that we are “not in a recession”. But, by definition, we can’t possible know we are in a recession until we’ve already been in it for at least 9 months. Of course, by the time we know we’re “officially” in a recession, we’re usually out of it. For the formal definition see here: The Definition of Depression and Recession.

In the 19th century, popular language didn’t use the word recession. Typically words used before 1929 to describe a contraction were either “panic” or “depression”. The contraction that began in 1929 was so severe it came to be called The Great Depression. The Great Depression was so severe and so long, that the word “depression” gained an extremely negative and emotional connotation. Since then, economists have tended to avoid using the word “depression” because it has such negative emotional connotations. Now, economists may use the word “depression” to describe a severe and very long-lasting recession, or a recession that economy cannot recover from for at least 3-10 years. The word “depression” has no formal definition like the word “recession” does. Politically, politicians out-of-office are likely to describe a current recession as a “depression”, just as the in-office politicians are likely to call a current recession a “slight slowing of growth”. Both are simply political campaign exaggerations.

Sometimes the “official” dating of recessions can cause confusion. That’s because even though a recession might have ended and growth resumed, the economy may not have fully recovered yet – as a result people still experience the economy as being “down”. See my explanation here of the recent recession dating: “It’s Over. Economists Are Speechless”.

Historical Evolution of the Business Cycle

Remember our goals for a macro-economy:

- Growth in production of real goods.

- Stable price levels and stable money.

- Cyclical stability – avoid recessions.

- Full employment of resources, particularly labor.

A good macroeconomic system is the one that can (and does) achieve these goals better than other systems. Historically, the record of the last 250 years of world history is clear. economies that are mostly, or at least partly, market-based have done the best towards these goals. However, the record is far from unblemished. As market-based economies grew through the Industrial Revolution, they achieved huge increases in growth – real output soared. But it seemed that the business cycle worsened. Market-based economies have been prone to up-and-down, boom-and-bust cycles throughout the past 200 years. At times, there have been periods of high unemployment. At other times, high inflation or even deflation. And a few times, such as The Great Depression, it seemed that a market-based economy might fail completely.

One policy issue that has persisted throughout the growth of market-based economies, is the question of what is the role of government in a market system? Should government manage the economy? Can a government manage the economy? What happens if government doesn’t get involved in the economy? Will a market economy, totally free of government controls, achieve these major goals, or will it self-destruct? Markets began to become more important with the Industrial Revolution. And ever since then, economists have been researching and theorizing about these policy questions.

The Business Cycle Is A Battleground For Economic Theories

Concerns about the first three goals, growth of GDP, price stability, and full employment, come together when focusing on the business cycle. Obviously the long-run growth rate of GDP is really the compounded series of short-term growth rates. But it’s more complex than that. Historical evidence (along with considerable theory) indicates that high growth for prolonged periods can bring inflation but will eliminate unemployment. The reverse is also true. If growth is too slow or even negative, then unemployment rises but inflation is unlikely. It’s worse if deflation happens since deflation triggers its own debt deflation-depression-high unemployment cycle.

Historically there has appeared to be a trade-off between high unemployment with low inflation vs. full employment with high inflation. Since stabilizing the business cycle at an acceptable level of growth involves all of our macroeconomic goals, it is the primary focus of most macroeconomic theories. Economists of different “schools of thought” have been debating the causes and dynamics of the business cycle for 200 years with little agreement.

Recession as GDP-below-Potential GDP

There are two ways economists tend to think about or describe the potential of the economy if it were functioning as well as it could. One is to look at employment, particularly the unemployment rate, to see if the economy has provided a job opportunity to employ everybody who wants and is available to work. This view depends on the unemployment rate which we will look at below.

The other common approach is to try to estimate the “potential GDP” and compare it to the actual GDP. This approach gives us an idea of how much additional GDP (more goods and services!) we could have had if only we could have created job opportunities for everybody. For a closer look at where the U.S. stands today relative to potential GDP see here.

Goal: Full Employment

There is still one major goals left: full employment of our resources. Typically, we measure how well a society achieves its goal of full employment of resources by looking at how well it is using its labor resources. Part of the reason for this goal is humanitarian: if some people are unemployed, it’s hard for them to live. But there’s a broader, more macro-oriented rationale as well: the economic problem. As a society, we have unlimited wants, but we have limited, scarce resources. Doing “the best we can” means making the best use of all our resources. The most important resource any society has is its available labor. For a society to reach its production possibilities, it must use all he available labor, and ideally, use that labor efficiently.

To measure how well society is using the available labor would seem to be an easy issue. It would appear that a simple percentage number could tell us how what portion of our available labor force is not being used, or is not “employed”. Indeed, this is the concept behind the most commonly used employment measure: the unemployment rate.

At its simplest, the unemployment rate is the “number of unemployed workers” divided by the “total labor force – the number of available workers. Of course we typically convert this division into a percentage number. This unemployment rate gets tremendous publicity. It is published for the previous month by the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Government on the first Friday of each month, along with a slew of other employment related data in the “Monthly Employment Report”. Unfortunately, like GDP, the unemployment rate is not a perfect measure. It may be the best we have, but it has flaws. It shouldn’t be regarded as a precise measurement. It’s only an approximation. It is subject to errors. More importantly, the way it is calculated leads to the potential for changes in the unemployment rate to give deceptive feedback about how the economy is doing.

In concept, the unemployment rate should tell us how well we are using our available labor resources. A low and decreasing unemployment rate should indicate a growing economy that’s creating opportunities for all workers. A high and increasing unemployment rate should indicate a slowing economy that’s entering a contraction and not providing opportunities. In general, over the long haul, the unemployment rate tends to do this. But changes in the unemployment rate can also provide distorted signals. It is possible that a contracting economy would actually show a decreasing unemployment rate for a while. Likewise, an economy that suddenly starts growing may show an unemployment rate that is increasing for a while. To better understand how this can happen, see the Closer Look on Unemployment Measures.

Economists do follow and use the unemployment rate statistics closely, particularly when looking at longer-term trends. However, in the very short-term, most economists also look closely at the absolute number of new jobs being created each month. In other words, while unemployment rate is important, the month-to-month increases in the total number of employed workers is also very important. Often the change in total employment will help identify when the unemployment rate is giving a distorted signal about the economy.

Types of Unemployment: Why are people unemployed?

Not all unemployed workers have the same effect on the macroeconomy. A lot depends on why the workers are unemployed. For this, economists identify four types or groups of unemployed workers based on why or how they became unemployed. There are no official statistics published about these different types of unemployment. Instead, these are analytical categories that economists use when doing small surveys or when theorizing about the dynamics of the economy. Nonetheless, it is important to understand the four types.

- Seasonal Unemployment – Some workers become unemployed because their jobs are seasonal. For example, ski resort workers are often unemployed in the summer. Summer camp workers are unemployed in winter. Many outdoor construction jobs disappear in the winter months, also. Seasonal unemployment tends to be predictable, and conceptually, isn’t a real macro economic policy worry. The jobs will return next year when the season returns. Fortunately, advanced statistical techniques allow economists to remove much of the effects of seasonal unemployment from reported unemployment and employment data. This is what is meant by “seasonally adjusted data”.

- Structural Unemployment – Some workers are unemployed because of long-term changes in the structure or technology of the economy. For example, at one time, the economy needed large numbers of railway workers. But as the economy increasingly shifted towards shipping goods by trucks and people by airplanes, we didn’t need as many railway workers. They became unemployed. Some of them had specialized skills that could only be used with railroads. Even if the economy was booming, these specialized workers would be unemployed until they developed other skills. Macro economic policy cannot change structural unemployment. Only job retraining, education for other jobs, and moving of workers can remedy structural unemployment.

- Frictional Unemployment – On any particular day some people are unemployed because they are looking for jobs AND there are open jobs for them. The job-seeker and the employer simply haven’t found each other yet. As most of you know, finding a job isn’t an easy process. There’s a lot of searching and interviewing going on. At a macro-economic level, these “workers-between-jobs” are good. It’s part of the process of the economy finding the right job for the right workers. Ideally, we do no want to eliminate frictional unemployment. If there were no frictional unemployment, then that would mean there were no workers looking for and being interviewed for better jobs. The economy would be stagnant. From a macro economic policy standpoint, frictional unemployment is OK.

- Cyclical Unemployment – This is the type of unemployment we want to avoid. Cyclical unemployment happens when the business cycle is either contracting or just starting to recover. We fully expect the economy to have need for workers with these skills, but right now the employers aren’t doing enough business to employ them. Workers who get laid off during a recession are the classical example of cyclical unemployment. We want macro economic policy to eliminate cyclical unemployment.

How Can 4 or 5% Unemployment Be “Full Employment”?

Understanding these four types of unemployment helps to explain why economists can say an economy that has reported unemployment of perhaps 4.5% is actually at full employment. The economists are not saying that 4% is close enough and that these unemployed workers don’t matter. Economists describe 4% to 4.5% unemployment as being full employment because it estimated that frictional unemployment is approximately 4%. So, if the reported actual rate is 4% and we estimate that frictional unemployment tends to run around 4%, it stands to reason that there is 0% cyclical unemployment. It should always be kept in mind that we only have estimates of how much unemployment is frictional – there is now way to formally measure it. Throughout the rest of the course we will often refer to the economy either being at “full employment” or “having substantial unemployment”. What we will mean in practical terms is that an economy at “full employment” is reporting approximately 4-4.5% unemployment. Anything greater than a reported 4% unemployment rate is likely to be cyclical or structural unemployment.

Reading Guide – Assigned Readings

In addition to the Jim’s Guide (above), you should read and study in your Mandel Economics: The Basics textbook:

Chapter 9 – Business Cycles, Unemployment, and Inflation

JIm’s Comment: This is a relatively short chapter, yet it is packed with very good information. Read all of it closely. Figures 10.2 and 10.4 are very important but Figures 10.7 and 10.8 can be safely ignored.

Practice Quiz

Click here for the Unit 9 practice quiz. The practice quiz will open in a new tab/window.

Worksheet

Unit 9 Worksheet – Data and Directions. After you complete the data problems on this worksheet page, you should answer the questions and enter your answers in learning mgt system (Moodlerooms at HFCC).

Closer Look

A tutorial from Jim’s macro course is helpful to explain how unemployment rate is calculated. This may be helpful for the worksheet exercise. See here.

Some videos if you need further explanation or clarification:

What’s Next?

In the next unit we take a look at some of the options for the government to be able to help stabilize the business cycle.