Jim’s Guide for Unit 5: Competition and Market Structures

Economists, in general, are very enthusiastic about competition. Competition is a good thing, at least for society as a whole economically. Why? Because it is efficient. And efficiency helps society make the most of its scarce resources.When the conditions are right, markets that are highly competitive force all firms to be very efficient. Competition between firms also makes the customer “king”. When firms compete, consumers ends up being the real bosses, the ones who decide what should be produced and in what quantities.

Highly competitive markets are also paradoxical. Firms don’t start out with the objective of being efficient and they don’t really intend to make the consumer the “boss”. But it turns out that way IF firms have to compete to get the customers’ business. What firms really try to do, of course, is to maximize their own profits. But, if the conditions for perfect competition exist, then we get a very paradoxical result: firms are trying to maximize profits, but none of them actually make any profits. They just earn enough accounting profits (zero economic profits) to stay in business. As a result, unlike in sports, in business firms do not want to compete. But they often must compete to survive. Profits are higher where there is less competition. But sometimes the conditions of the industry make for more competition.

Different markets and different industries face different levels, forms, and intensity of competition between firms. Economists call these different kinds of conditions market structures. We start this by unit we’re going to look at the market structure economists use as the “standard” to measure the performance of all markets: Perfect Competition. Sometimes it’s called Price Competition, sometimes Pure Competition, but it has the same result: efficiency and zero economic profits in the long-run.

Looking Ahead: Market Structures

In this unit we will study four of the more common market structures that exist. These are:

- Perfect Competition

- Monopoly

- Monopolistic Competition

- Oligopoly

It’s useful to think about these four market structures as different locations on a spectrum. Imagine a spectrum of “competitiveness”. At the moment we haven’t defined “competitiveness”, but imagine a spectrum such as shown below that runs from extremely competitive, where there are lots of competitors intensely fighting each other and very evenly matched, to completely uncompetitive. In the completely uncompetitive situation, there’s absolutely no competition between firms because there’s only one firm. There’s not even the threat of a record firm starting up.

Pure Price Competition is what economists call the theoretical case of complete and intense competition. Some economists use the term Perfect Competition for pure price competition. At the other end, Monopoly is the theoretical result of having absolutely no competition – the other end of the spectrum. In the real world, very few markets or industries truly meet all the conditions of “perfect competition” or of “monopoly”. In fact, no real world industry or market is “perfectly competitive”. Perfect competition is only an idealized hypothetical situation intended to focus attention on the socially beneficial effects of competition.

In the real world, most markets and industries are in between these two. They have varying degrees of competition. If the market has a lot of competition, but not quite as much as the theoretical ideal of “perfect competition”, we call it “monopolistic competition”. It’s competition, but it’s just to the monopolistic side of perfect competition. Some books call this “imperfect competition”.

In some situations, the number of competitors gets very small – approaching one, but not quite. This is called an oligopoly. It’s perhaps the most interesting for economists to research because it’s the most unpredictable.

In this unit we start with the ideal of a perfectly competitive market. In the next unit we jump to the polar opposite: monopoly. After that we examine the two in-between cases. It’s these somewhat competitive situations, the in-between cases of Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly that you and I most likely encounter in the real world, but to understand them, we need to look at the theoretical extremes.

When Does Perfect Competition Exist?

Perfect Competition is an abstract, theoretical model of a market structure. In the real world, there aren’t any true, fully perfect competition markets. However, there are markets that tend to come close. Four conditions create Perfect Competition. Often these conditions are called the characteristics or assumptions of perfect (pure price) competition model.

First, there are so many small producers (firms), that none of them has any significant influence on market pricing. For example, imagine a small farmer (somebody whose farm is small, not necessarily that they are short!). The market for corn in the United States is so huge, that the market equilibrium price won’t change, regardless of whether this particular farmer decides to grow another acre of corn or not. This condition of each firm being so small that they are insignificant relative to the market is what makes the MR curve horizontal or perfectly elastic. Each firm can produce what seems to them like a much large quantity of output, but it really isn’t much more compared to the market. As a result, the additional output the firm produces can be sold at the same price as smaller quantities of output.

Second, imagine a market where all firms are selling absolutely identical products produced in exactly the same way. For example, if you buy a share of stock in General Motors Corp, it doesn’t matter who you buy it from – each share is exactly the same as another. When all firms make products that are essentially identical, they are called homogeneous products. The assumption of homogeneous products is important. It means that all firms will be selling their products at the same price. If all firms’ products are identical to each other, then customers can only choose between firms by choosing the lowest price. Any firm with a slightly higher price loses all of its customers.

Thirdly, in perfect competition, there are no barriers to entry or exit. This means new firms can easily and quickly get into the industry, as well as existing firms can easily quit. We’ll see that in the long-run, this is an important condition. As a result of no barriers to entry or exit, the industry will, in the long-run, not make any economic profits at all.

Finally, some books ignore an important fourth condition or assumption of perfect competition. I summarize it as no secrets allowed, but some economists call it “perfect information”. This condition means that if a firm discovers a new, lower cost way of producing they can’t keep it a secret. All the other firms will copy the innovation. As a result, all firms have essentially the same cost curves. Similarly, no firm is able to fool or cheat customers either.

Short-Run Perfect Competition, Profits, and Entry

In the short-run, all the many small firms are at the mercy of the market price. Total market supply and demand sets a market price and each firm sells at the market price or it doesn’t sell at all. Each firm then uses this price (which is also their marginal revenue) to decide what quantity to produce (Q) using the MR=MC logic previously described. Then each firm calculates how much profit it earned. If the market price is high enough, then it is possible each firm might be making a positive profit. It so, each firm is probably happy with the outcome — after the goal of the firm is make profits. But the existence of economic profits among the firms in this industry acts like a big red flag to all the firms and entrepreneurs outside this market/industry. Firms outside this industry see the economic profits and want to get some too. So these outside firms enter the market,When new firms enter the market, it expands the number of firms in the market and shifts the market supply curve to the right, lowering the market price. With the market price now lower, all the firms in the industry must now re-calculate what quantity to produce (where MR=MC), and then re-calculate how much profit they made.

Long-Run Outcome Of Perfect Competition

The outcome of having these conditions, combined with firms making rational profit-maximizing decisions, has an interesting result. As long as these three conditions hold true, then by having all firms try to maximize their own profits, none of them will make any profit in the long run. Even more significant, is that each firm will be led to produce the product as cheaply and efficiently as it knows how. Not because it wants to, but because that’s how to maximize profits in the short run. Unfortunately for the firms, but fortunately for consumers, those short-run profits attract new competitors. New competitors don’t have any way to sell in the industry unless the cut the price to attract customers. The existing firms then have to follow the price cut (the products are all identical, remember). And there go the profits. The price competition and new entry of firms keeps all the firms from making long-run economic profits.

Perfect competition is the standard by which economists evaluate the performance of all other market structures. Perfect competition, price competition, is efficient.Customers end up getting products made at the lowest possible cost for the lowest price.In the long-run, firms don’t make any economic profits — they make only enough accounting profit to keep them in business. Needless to say, firms aren’t too happy about perfect competition. Who wants to work that hard and then not make economic profits? Most firms, if it is possible, will avoid competing on price in perfect competition with other small firms who make identical products. In the next few units we will study the other market structures in which firms try to avoid competing on price alone.

Competition brings out the best in products

and the worst in people.

– David Sarnoff Radio & TV Pioneer

Monopoly

I had no ambition to make a fortune; mere moneymaking has never been my goal. I had an ambition to build.

I had no ambition to make a fortune; mere moneymaking has never been my goal. I had an ambition to build.

– John D. Rockefeller, founder of Standard Oil Company, a monopoly

One in economics, the other in politics, refuted the liberal dream of universal happiness

through individual competition, substituting monopoly and the corporate state, or at least movements toward them.

– Bertrand Russell, Freedom Versus Organization, 1814 to 1914,

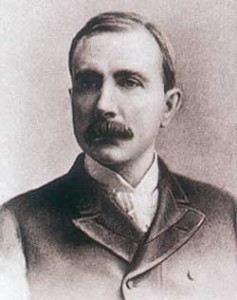

At the start of this century in 2000, Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, was widely reported to be the richest man in America now. He’s still very rich and close to the richest, but not quite. But 100 years ago, at the start of another century, the richest man in America was John D. Rockefeller. It’s difficult to compare fortunes 100 years apart due to the effects of inflation, but some economists have estimated that Rockefeller’s fortune at its peak was perhaps 3-4 times as large as Gates’s fortune today. That’s a lot of money. Rockefeller wasn’t alone, though. Rockefeller’s time was known as the “era of Robber Barons”. Others accumulated huge fortunes: Andrew Carnegie,Thomas Edison, Cornelius Vanderbilt, J.B. Duke, and others.

How did these people accumulate so much money? One word: Monopoly. In the last unit we studied how the forces and conditions of perfect price competition keep firms from being able to actually earn economic profits over the long-run. Yes, a firm in perfect competition might make some economic profits in the short run if market prices are favorable, but price competition and entry of new competitors eventually put an end to the profits. But, under conditions of monopoly, a firm doesn’t have to worry about competitors. A monopolist doesn’t have any competitors. There is no competitor to undercut price. Truly successful monopolies are also able to prevent any future would-be competitors from entering the industry.

When monopoly conditions exist and the product is in demand by consumers, the monopolist can (and usually does) make extraordinary profits. In the late 1990′s, Microsoft controlled over 98% of the market for personal computer operating system software. That’s effectively a monopoly and it led to the huge monopoly profits that became Bill Gates fortune. In the 1890′s, John D. Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil, controlled over 98% of the market for oil and gas in the U.S. Standard Oil’s monopoly profits became the source of Rockefeller’s fortune.

Monopoly: The Goal for Profit-Seeking Businesses

I described the following “spectrum” of competitiveness. We saw how Pure Price Competition (Perfect Competition) led to a long-run outcome where firms don’t make any economic profits. Obviously, since firms and entrepreneurs want to maximize profits, they would rather not compete in Perfect Competition, if at all possible. In this unit we look at the complete opposite situation: Monopoly. In a Monopoly, there is no competition. A monopolist doesn’t have to worry about being undercut on price and the most successful monopolies don’t have to worry about new entrants into the industry lowering market price.

For business firms (and their owners), Monopoly is the goal. A true monopolist maximizes profits by following the same decision process as other firms. In other words, a monopolist will follow the marginal revenue = marginal cost logic to find the quantity to maximize profits. Likewise, a monopolist calculates profits as (P-ATC) times the Q sold. The difference is that a monopolist doesn’t have accept some a price driven down by competition. The monopolist can set the price. There are some limits on how much a monopolist can charge (see below), but essentially a monopolist can pick his/her own price. this time, the conditions of the market result in the Monopolist making very large economic profits. What’s more, since one of the conditions is barriers to entry, the monopolist doesn’t have to worry about new competitors coming into the market and cutting prices (and thereby the profits!). The monopolist just keeps on making economic profits over the long run.

For business firms (and their owners), Monopoly is the goal. A true monopolist maximizes profits by following the same decision process as other firms. In other words, a monopolist will follow the marginal revenue = marginal cost logic to find the quantity to maximize profits. Likewise, a monopolist calculates profits as (P-ATC) times the Q sold. The difference is that a monopolist doesn’t have accept some a price driven down by competition. The monopolist can set the price. There are some limits on how much a monopolist can charge (see below), but essentially a monopolist can pick his/her own price. this time, the conditions of the market result in the Monopolist making very large economic profits. What’s more, since one of the conditions is barriers to entry, the monopolist doesn’t have to worry about new competitors coming into the market and cutting prices (and thereby the profits!). The monopolist just keeps on making economic profits over the long run.

The Conditions of Monopoly

In a monopoly, there is only one firm. This one firm supplies the entire market. This one firm, the monopolist, is the market supply curve. There is no competition. But, for a monopolist to turn this lack of competition into truly large economic profits there are other conditions that must exist too.

Two conditions are necessary for a monopolist to be able to charge high prices and reap large economic profits. The first is that barriers to entry must exist and they must be strong. Usually, this means some kind of legal restriction or privilege that makes the monopolist the only game in town. In other cases, it means literal control over some critical resource. Barriers to entry prevent other firms from getting into this particular market. Since other firms cannot enter, there is no competitive threat and no reason for a monopolist to be restrained in pricing the product.

The other condition to making substantial economic profits, is a friendly demand curve of consumers. Ideally, the monopolist wants a substantial demand curve that is relatively inelastic for large volumes. An inelastic demand curve means customers are willing to pay substantial prices for a product they view as a necessity and that doesn’t have good substitutes. When demand is inelastic, it means consumers don’t have much choice – they feel they “have” to buy the commodity. It’s this inelastic demand combined with a lack of competition that gives the monopolist her power.

Monopoly, while very good for the monopolist, is very damaging to the welfare of everybody else. Indeed, monopoly can be so lucrative and so profitable, that some businesses will do almost anything to obtain it. As a result, most modern industrialized societies, such as the US, the European Union, Canada, and others attempt to control, regulate, or prevent unrestricted monopolies from occurring. Your book discusses how to control monopolies in the chapter on anti-trust (look it up in the index). We won’t study anti-trust during this semester, but if you have any interest in monopolies, particularly the Microsoft case, you might want to look at that chapter. It is entirely optional, though.

Barriers to Entry: The Key to Monopoly Profits

It isn’t enough to have a product that consumers demand and to be the only source of the product. For a monopolist to charge high prices and earn large economic profits for any extended period of time, the monopolist must be protected by barriers to entry. Sometimes, the sheer economies of scale of the technology needed to produce the product makes a sufficient barrier to entry. But the most reliable and the strongest barriers to entry depend on either gaining exclusive control of a critical resource needed for production or having the government prevent competitors from entering.

Some of the most successful monopolies have relied on gaining powerful control over some critical resource. For John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil, the key was exclusive deals with railroads that provided significantly lower freight rates for Standard Oil and higher rates for any would-be competitors. For Cecil Rhodes, the founder of the DeBeers Diamond cartel, the original key resource was exclusive rights to diamond mines in South Africa. Later he and Ernest Oppenheimer gained exclusive control over the wholesale marketing of diamonds in London and Belgium. Microsoft gained exclusive access to being pre-installed on computers by signing exclusive contracts with PC makers. The U.S. government later sued and convicted Microsoft of making illegal contracts with these PC makers, but by then the fortune and monopoly status had been achieved.

While the US government has, at times, fought monopolies such as Microsoft, Standard Oil, and American Tobacco, it also creates many monopolies. For example, an effective barrier to entry can be a patent issued by the government. In other cases, governments often grant exclusive rights to some firms and prohibit competition. For example, for over 80 years, AT&T had a monopoly on long-distance telephone service. For at least 60 years, until 1984, AT&T had a monopoly on all telephone service.

Monopoly is indeed very attractive to the lucky firm that achieves it. But, looked at from a social perspective, monopoly is definitely very un-attractive. A monopolist earns higher profits by charging a much higher price. Consumers must pay this higher price. Consumers also suffer because a smaller quantity will be produced. Some people who would have been able to afford a competitively priced product will not be able to afford the product and will have to do without.

A monopolist also produces inefficiently. Monopolists do not produce at the lowest possible ATC, because they can maximize profits with a smaller quantity. Monopolies are also allocation inefficient because consumers aren’t really making the decisions on how much to produce.

Yes, a successful monopoly can accumulate enormous economic profits and private fortunes such as Standard Oil and Microsoft. Sometimes, these private fortunes are put to good charitable uses later. John D. Rockefeller endowed and started several major universities (Univ. of Chicago, Spellman College, Johns Hopkins, and others). Andrew Carnegie built hundreds of libraries throughout the US. Bill Gates has now pledged to use his fortune to fight AIDS and other diseases. But these fortunes didn’t come from nothing. These fortunes come from the higher prices that millions of customers had to pay because they didn’t have any choice. Any social evaluation of monopoly must take account of the opportunity cost of those higher prices and lost output.

Most business firms might dream of being a monopolist, but realistically they can’t. Most products made by most firms have good substitutes. Entry is possible in most real-world markets, making long-term monopoly impossible to maintain. Nevertheless, most firms in the real world don’t surrender, give up, and resign themselves to a life in perfect competition. These firms find ways to carve out little “temporary” monopolies instead of competing on price. In the next unit, we take a look at this real-world phenomenon called monopolistic competition.

Monopolistic Competition

The engine which drives enterprise is not thrift, but profit.

The engine which drives enterprise is not thrift, but profit.

– John Maynard Keynes

The strongest principle of growth lies in human choice.

– George Eliot (pseudonym of Mary Ann Evans Cross)

Visit your local supermarket, mall, or giant big-box store and one feature stands out: choice. As consumers in the early 21st century in an industrialized economy, we certainly have choice. There is a seemingly endless variety of different products with different features and different characteristics from which we can choose what best suits us. Economists have a term for this phenomenon: product differentiation. For consumers, the downside is the difficulty in deciding just which item is best for us – as the gentleman to the left is trying to decide. The big benefit of product differentiation for consumers is that we get many new products and products that are tailored to exactly our needs.

Visit your local supermarket, mall, or giant big-box store and one feature stands out: choice. As consumers in the early 21st century in an industrialized economy, we certainly have choice. There is a seemingly endless variety of different products with different features and different characteristics from which we can choose what best suits us. Economists have a term for this phenomenon: product differentiation. For consumers, the downside is the difficulty in deciding just which item is best for us – as the gentleman to the left is trying to decide. The big benefit of product differentiation for consumers is that we get many new products and products that are tailored to exactly our needs.

For the firms that make the products, though, the benefit of product differentiation is that it helps the firm avoid perfect competition. When firms all offer slightly different products, the conditions of perfect competition don’t exist. Instead, monopolistic competition exists. Unlike perfect competition, firms in monopolistic competition may sometimes earn some economic profits. But the key to these possible profits lies in making the product different (and better) than that offered by other firms. Of course it’s not enough to just be different, the product has to be different in way that consumers think is better.

Welcome to the Real World

Perfect Competition and Monopoly are theoretical models of two very extreme, very different market structures. Both models are theoretical constructs with strict assumptions and conditions. In the real world, very few markets conform perfectly to the rigid and extreme assumptions we made in our models. For example, in monopoly we assumed that there was only one firm and that it was impossible for another firm to compete. Real world monopolies often do have a competitor or two, it’s just that the competitor is so small compared to the monopolist, that the monopolist is practically the only firm. Even at the height of Microsoft’s monopoly, it was still possible to buy an Apple, but less than 2% of all buyers did.

In the past, over 100 years ago, or in less industrialized societies,perfect competition was and is reasonable model of some markets. But in today’s modern industrialized world, the perfect competition model, with its assumption that all products by all firms are homogenous (perfectly identical) doesn’t reflect the reality of how most modern firms compete. In today’s world, most firms compete by either making their product different, or by advertising heavily in an attempt to convince consumers that the product is different.

Monopolistic competition is a model that attempts to capture the realities of how modern firms actually do compete with each other. It places great emphasis on product differentiation.

Product Differentiation: My Product Is Different, It’s Better — So Pay Me More

Product differentiation means that each product is slightly different from what’s offered by competitors. These differentiated products still compete with each other in the sense that the consumer chooses between them (considers them substitutes for each other). But the nature of this competition is critically different from perfect competition. In perfect competition all firms produced the same, identical product. Since the products of competing firms were identical (homogenous), buyers simply choose whichever firm offered the lowest price. Firms that didn’t offer the low price didn’t sell anything, so soon all firms are forced to lower prices. Eventually prices are forced down to the level of average costs, meaning that none of the firms in perfect competition make any economic profits. Needless to say, the firms are not’ too happy about this result. Firms exist to maximize profits and they aren’t too happy when that means no profits at all! The profit-squeeze that results from competing on price drives firms to seek any way to avoid perfect competition. Of course for firms, the ideal would be monopoly, but monopoly is difficult to achieve.

If monopoly isn’t an option, and the firm still has numerous competitors, then it has to find a way to compete that doesn’t involve cutting the price. Product differentiation is the answer. By making the product different from what competitors offer, it’s possible to develop a product that’s (maybe) better. Better in this case, means a product the consumer wants more than what the competition offers — a product that better suits consumer needs. If the consumer thinks a product suits them better, if the consumer “prefers” it, then consumers (at least some of them) may be willing to pay a slightly higher price for the product. A slightly higher price is all the firm needs – it’s found a way to avoid competing on price alone. How much higher of a price depends, naturally, on how much better the consumer thinks the product is. This is the motivation for product differentiation – to find a way to compete that doesn’t involve cutting the price. Since the price doesn’t have to be cut, it is sometimes possible to earn some economic profits. The result is what we call monopolistic competition.

Long-Run: Only The Paranoid Survive

The real difference between monopoly and monopolistic competition comes in the long-run. Monopoly has strong entry barriers preventing new firms from competing. Perfect competition has no entry barriers. Monopolistic competition has very weak, if any, entry barriers. In the long-run, the emphasis in monopolistic competition is on the competition part.

In practice, this means that if an individual firm in monopolistic competition does successfully differentiate the product, and, as a result, does earn some economic profits, the other firms will quickly copy the successful product. Once other firms copy the successful product, it’s not different any more. It’s no longer unique. The firm is now back to competing on price alone. And when price competition appears, profits disappear.

In practice, this means that if an individual firm in monopolistic competition does successfully differentiate the product, and, as a result, does earn some economic profits, the other firms will quickly copy the successful product. Once other firms copy the successful product, it’s not different any more. It’s no longer unique. The firm is now back to competing on price alone. And when price competition appears, profits disappear.

Most firms know that successful products will be copied. So the wise and forward-thinking firms usually try to develop new and additional ways to improve the product. Just as the competition copies the “better” product, the firm brings a new, improved, even better version of the product. One firm that has earned enormous profits over 30 years is Intel. The photo to the right shows just some of the different logos for the different “new, better, faster” computer processors that Intel has introduced over the years. Each time, it took the competition from a few months to a couple years to copy the product. Just as the competition came out with processor chip equivalent to Intel’s, Intel would introduce an even newer and faster chip. Intel’s chairman eventually wrote a book describing this strategy. He titled it, Only The Paranoid Survive. Intel was constantly researching and developing new and better products in the fear that competition was catching up. Eventually, they did.

If You Can’t Make A Better Product, Tell’Em Yours Is Better Anyway

Of course, it’s not always possible to keep developing better and better versions of your product. And sometimes, the essential differences between one firm’s product and another firm’s version of the product aren’t very great. For example, consider Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, RC Cola, and most store-brand colas. The essential products are different – each one does tastes slightly different and has a slightly different formulation. But the differences are very slight and many, perhaps most, consumers can’t tell the difference. So how do these firms avoid pure price competition? One way is by differentiating on non-physical features such as the location of vending machines. But the bigger tactic used is advertising. Lots of advertising.

Why advertising? Because repeated advertising can create the image of a different or better product in the mind of the consumer. All advertising isn’t intended to do this. Some advertising is simply an attempt to inform consumers about legitimate product differences or simply how and where to buy the product. But a lot of advertising is intended simply to persuade consumers of some psychic benefit to the product, or some image. That’s what most Coca-Cola and Pepsi advertising is all about. It’s an attempt to get consumers to prefer that particular brand, even if it costs more.

One feature of all product differentiation is product branding. Indeed, without brand names, advertising-based product differentiation would very difficult. Consumers wouldn’t be able to identify their “preferred” product if it didn’t bear the brand name.

Performance: How Does Monopolistic Competition Do?

Monopolistic competition can be profitable and beneficial for a successful individual firm. But how does it perform for society? Monopolistic competition isn’t as efficient socially as perfect competition. It definitely isn’t as allocation efficient. A monopolistic competitor with successful product differentiation will be pricing the product at slightly higher than marginal cost. This isn’t allocation efficient.

All firms in monopolistic competition are not production efficient, either. Whether successful or not, all firms are attempting to differentiate their product. Some try research and development and attempt to find new, innovative products. Other firms are advertising in trying to differentiate. Either way, the firm spends a lot of money on either R&D or advertising or both. These additional activities raise a firm’s fixed costs and total costs above what they would be in perfect competition.

From a social perspective, the spending on R&D could be considered a positive. R&D can lead to innovations and new products which benefit society. How ever, there is no assurance that the R&D spending is being spent efficiently. Advertising expenditures, or at least a significant portion of them, are very likely simply a waste of resources without a net increase in social welfare.

The two redeeming characteristics of monopolistic competition are that whatever monopolistic profits are achieved tend to be relatively short-term. Without entry barriers, competition returns and prices drop. The best feature of monopolistic competition, though, is innovation and variety. We owe the huge variety of products that we have in stores to the effects of monopolistic competition.

The customer can have any color

he wants so long as it’s black.

– Henry Ford, quoted not long before General Motors

overtook Ford Motor as the largest car maker

Oligopoly

People of same trade seldom meet together even for merriment and diversion but conversation ends a conspiracy against the public or in some contrivance to raise prices.

– Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

You, like most students, have probably played the board game Monopoly at some time (personally, I always wanted to be the race car token). Technically speaking, the game is misnamed. If the game had been invented by an economist, she would probably have named it Oligopoly. As soon as someone actually achieves a monopoly in the game Monopoly (meaning they own all the property), the game is over – the monopolist has won. But until a monopoly is achieved, the game actually consists of just a small number of players, each trying desperately to become the monopolist by outwitting each other, but each also having to watch out for what the other players are doing. The real-world market structure called oligopoly works pretty much the same as the board game of Monopoly.

Oligopoly: Getting Close to Monopoly

So far we’ve described 3 markets structures. Perfect Competition involves many small firms competing purely on price. Monopolistic Competition also involves many firms, but now the firms are competing through product differentiation so that some monopolistic profits are possible. At the other extreme is the very profitable Monopoly, where no competition exists.

In this unit we consider what happens when the number of firms has dropped to only a small number. If there’s only one firm, that’s a Monopoly, and no competition exists. What happens if there are only 2 firms though? Or if there are only 3 or 4 firms? Do they still compete? How? And what’s the outcome? These are the questions we consider in looking at Oligopoly.

Oligopoly: The Critical Condition (and the Implications)

The essential feature of oligopoly is that there are only a small number of firms. All the other characteristics of oligopoly result from this fact.

Since there only a few firms, then logically, each firm is relatively large compared to the total market. For example, when there are 500 firms each firm has less than 0.2% market share on average. But if there are only 4 firms, then each firm has an average market share of 25%. Market shares that large mean that each firm’s decisions about price and quantity to produce can easily affect the overall market supply. Change the market supply and you change market equilibrium price for everybody. In other words, in oligopoly, each firm knows it has the power to lower the market price that it’s competitors get paid. Even more significant, each firm knows that if it raises price and the few other firms that exist follow suit, then the market price will rise to almost the price a monopolist would charge. This means that the results of each firm depend on what the other firms decide. Each firm is therefore interdependent.

The Nature of Competition Changes – The Dream of Monopoly Beckons

Each firm is interdependent, meaning each firm’s profits depend not only on what price and quantity it chooses, but also on what price and quantity the small number of competitors chooses. This changes the nature of competition in oligopoly dramatically. In Perfect Competition, each firm competes on price — survival depends on having low costs and being efficient. In Monopolistic Competition, success is possible by understanding the customer better and developing better products and advertising. But in Oligopoly, success depends largely on predicting what the other firm(s) are going to do and then making an optimal decision on price, quantity, or product design.

In oligopoly, products may be homogenous or they might be differentiated. Firms might compete aggressively on price, or they might not. It all depends on what each firm thinks the other firms will do and what options that leaves them. Because there are only a small number of firms, a new possibility exists that is totally impractical in Perfect or Monopolistic Competition. In these very competitive markets, there are too many firms to be able to coordinate the decisions of so many firms. That’s not necessarily the case in Oligopoly. Lurking in the back of the mind of every oligopolist is the knowledge that IF the few competitors were eliminated then the firm would be a monopolist and earn high profits. Also lurking is the knowledge that IF the few firms in the oligopoly could only coordinate their price and production decisions, then the group of them could earn monopoly profits together – they could be a shared monopoly. But, also lurking in the mind of every oligopolist is the uncertainty about whether the other firms will cooperate.

Strategic Thinking

In Oligopoly, everything depends on what each firm chooses. The market could end up resembling a shared monopoly with each firm earning a share of what a monopolist would have made. Or, the market could end up in bloody price-cutting competition as each firm undercuts the others in an attempt to force the other firms to lose so much money they go out of business, leaving only one firm left as monopolist. Or, the market could become stagnant and resistant to change as each firm is reluctant to “rock the boat” for fear of how the competitors will react. It all depends on what the firms choose.

But what each firm chooses depends on what that firm thinks the other firm will choose. Consider the situation of a duopoly (2 firm industry), a type of oligopoly, with Cogswell Cogs, Inc. vs. Spacely Sprockets. Before Cogswell chooses a price and production quantity, it needs to know the market price. But market price depends on what price both Cogswell and Spacely pick. So Cogswell needs to know Spacely’s price before it can choose its own best price. So Cogswell bases its price on what Cogswell thinks Spacely will charge. But Spacely bases its price on what Spacely thinks Cogswell will charge. But Cogswell knows that Spacely will do that, so Cogswell needs to know what Spacely thinks Cogswell will charge — which is based on what Spacely thinks Cogswell will think that Spacely thinks Cogswell will charge. And on and on. Each firm needs to “get inside the head” of the competitors. This is called strategic thinking.

Game Theory: Analyzing Strategic Thinking

Strategic thinking is a bit like looking at the image of a mirror in a mirror. You see an image of a mirror inside each image of a mirror in the mirror. Our ordinary graphic tools and models aren’t much help in analyzing this kind of situation. So economists (and other social scientists & mathematicians) have developed techniques called game theory. The Oscar-winning movie in 2001, A Beautiful Mind, is the biography of the John Nash, the economist who helped co-invent game theory. John Nash also won the Nobel prize for his contributions of game theory to economics.

Strategic thinking is a bit like looking at the image of a mirror in a mirror. You see an image of a mirror inside each image of a mirror in the mirror. Our ordinary graphic tools and models aren’t much help in analyzing this kind of situation. So economists (and other social scientists & mathematicians) have developed techniques called game theory. The Oscar-winning movie in 2001, A Beautiful Mind, is the biography of the John Nash, the economist who helped co-invent game theory. John Nash also won the Nobel prize for his contributions of game theory to economics.

In game theory, economists describe a situation or market by using the metaphor of a “game”. Just like a real-life game, there “rules” that are defined, players identified, possible strategies or decisions by those players, and then outcomes (or “payoffs”) are identified as the result of different possible strategies. These various strategies are analyzed, often using some sophisticated mathematical techniques, and the “best” options are identified for each player. Sometimes, the best choices for each individual player lead to outcomes that are less than attractive for the whole group.

Oligopolies lend themselves well to analysis using game theory. Some of the more common “games” that are played in real-world oligopolies are Follow-the-leader, Collusion, Price Signaling, and even Gin game (firms keep buying up smaller companies and then selling them). One particular game situation is called Prisoner’s Dilemma. It is a famous game theory “game” and we will study it closely in this unit.

Oligopoly Performance: Uncertain

Because everything in oligopoly depends upon what each firm thinks the other firms will do, it’s very difficult to predict the outcome (pricing or output) of any particular oligopoly. It all depends on who is “playing” the game. Oftentimes, the “game” itself can change. For example, in the 1950′s through the 1970′s, the U.S. Big Three automakers (Ford, GM, and Chrysler) played a very stable game of “follow the leader”. The leader was GM who set pricing levels and Ford & Chrysler followed. Other rules of the game included:

- It’s OK to compete on styling and horsepower.

- It’s not fair to compete on labor costs, productivity, quality, or fuel efficiency.

- The United Auto Workers (UAW) made sure all three companies had similar labor costs – for which the UAW was rewarded with above-average wages.

Unfortunately for the Big Three, the game expanded in the late 1970′s-1980′s to include Toyota, Honda, Nissan, Volkswagen, and Mercedes. These foreign firms didn’t “understand” these unwritten rules and began to compete on cost, quality, and efficiency. By the time Big Three executives understood the game had changed (I’m not sure they really know yet!), they had lost enormous market share and profits to the foreign companies, most of whom have now become large U.S. producers.

Oligopoly in the Real-World

Mergers and acquisitions by large corporations, financed by Wall Street, have greatly expanded the number of industries/markets that are effectively oligopolies. In the past 25 years, a wave of consolidation in many industries has reduced what used to be monopolistic competitions into oligopolies. For example, consider hair cutting and styling. Twenty years ago, barber shops and hair styling salons were definitely a monopolistic competition: thousands of individual salons each with a slightly different service depending on who the barber/stylist was. Now, despite the appearance of hundreds of brand names, the industry is on its way to consolidating into an oligopoly. It is interesting to check out this page where a website called Oligopoly Watch describes Regis Corp., one of the biggest players in the hair cutting business. Check it out, you’ll be surprised at how many firms you thought were independent are in fact owned by the same corporation.

This has happened in many industries. Consumer products in particular are very concentrated in the hands of a few large, global corporations. Much of this oligopolistic consolidation has happened in just the last 25 years. For a look at some major corporations and the many brands they own, check out the Oligopoly Watch Company Profiles.

Firms in oligopoly find that the most profitable strategy is not to focus on customers, new products, or new technology. Instead, firms in oligopoly seek to limit the entry of new competitors and to find ways to coordinate the behavior of the remaining few mega-firms. In this way the entire oligopoly industry can behave the way a single monopolist would behave: driving up prices, restricting output, and earning more-than-necessary economic profits. Increasingly this means spending large sums of money on lobbying, campaign contributions, and “political speech advertising”. While the sums spent to get their way in government may dwarf the money that individual consumers or households can spend, the sums spent by these firms are actually extremely profitable “investments”. They are “investments” in the sense that future profits are much higher as a result of the money spent on government, although no improved productivity or consumer benefits result. Examples of large oligopolies that have significantly increased their profitability in the last 20 years as a result of these “investments” in manipulating government include:

- “Big Pharma”, the large prescription drug companies (Medicare drug benefit, ACA Healthcare reform bill, patent laws, international trade treaties)

- “Big Oil” (environmental regs, leases on federal land, exemption from liability, tax subsidies)

- Wall Street and Big Banks (the bank bailout, lax enforcement of securities laws, subsidies, preferred tax rates, restrictions on competition, international trade treaties, elimination of decades-old regulations). Today only 5 banks own almost 90% of all banking business in the U.S.

- Hollywood and the commercial Music business (extension of copyright laws, international trade treaties, preferred tax rates and subsidies)

- In consumer goods, especially anything sold in a grocery store, there has been enormous consolidation. Thirty years ago, 50 firms produced and sold 90% of the goods in a typical grocery store (by sales volume). Now, only 10 firms control 90% of that volume. You might be surprised to see who really owns the brands you buy – take a look here.

Reading Guide – Assigned Readings

In addition to the Jim’s Guide (above), you should read and study in your Mandel Economics: The Basics textbook:

Chapter 5 – Competition and Market Power

Jim’s Comment: The entire chapter is required reading. In this chapter, focus more on the concepts and ideas. The analytical portions such as graphs and tables should be used to illustrate the concepts and not as the focus of the lesson. Pay more attention to being ablt to recognize when a firm is in each type of competition or market structure. Also pay attention to the social consequences of each type of market structure: do consumers get more or less produced? do consumers pay higher or lower prices? do firms make more or less profits?

Practice Quiz

Click here for the Unit 5 practice quiz. The practice quiz will open in a new tab/window.

Worksheet

The data, directions, and a description of the problem are here at the Unit 5 Worksheet. Answers to the questions can be entered and graded in the learning mgt system (Moodlerooms at HFCC). Go there to complete them.

Closer Look

Other Video Tutorials

Dr. Mary McGlasson of Chandler Community College in Phoenix, AZ (known as mjmfoodie on YouTube) has numerous videos which are pretty good. Here are the ones relevant to this unit.

What’s Next?

This unit concludes our micro-focus in this course. It’s time for a mid-term exam and some reflection on what you’ve learned so far. Then, in the next units we start to look at the big picture: the economy as a whole, or what we call macro-economics.